Radicality

& Dialogue

I am exploring the relationship between radicality and dialogue in communication and art.

Jan Motal

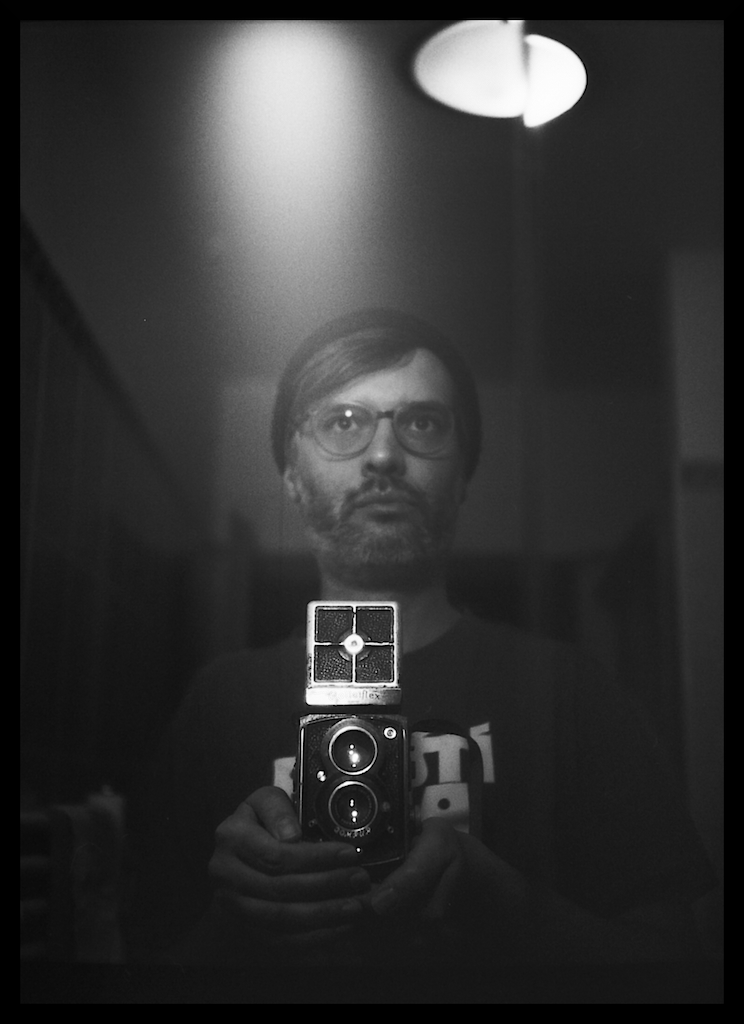

I write books and articles and teach philosophy, media ethics, and social critique. Alongside academic and public-facing writing, I work in experimental art—especially film, sustainab le and alternative photography, and their connection with performative forms. My most recent monographs are Radical Dramaturgy (2022) and Radical Theology (2024). I am part of the art collective Dílo and contribute to the magazine of the same name.

My long-term focus is the relationship between radicality and dialogue: how the need to go “to the roots” and formulate a radical critique of society can be joined with openness, reciprocity, and participation. I teach at universities in Brno and Olomouc, and at the Department of Media Studies and Journalism (Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University) I coordinate the Centre for Media Ethics and Dialogue.

I collaborate with the Endowment Fund for Independent Journalism, Future Memory Lab, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism, and the Network for the Protection of Democracy. I also serve on the editorial board of *Deník N* and am a member of the Initiative for a Critical Academia. I helped develop and organise a conference on ethics in documentary film as part of the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival.

Jan Motal

Píšu knihy, články a učím o filozofii, etiku médií a společenskou kritiku. Vedle akademické a publicistické práce se věnuji experimentálnímu umění – především filmu, udržitelné a alternativní fotografii a jejich propojování s performativn ími formami. Naposledy mi vyšly monografie Radikální dramaturgie (2022) a Radikální teologie (2024). Jsem součástí uměleckého kolektivu Dílo a přispívám do stejnojmenného časopisu.

Mým dlouhodobým tématem je vztah radikality a dialogu: jak potřebu jít „ke kořenům“ a formulovat radikální kritiku společnosti propojit s otevřeností, vzájemností a účasti. Učím na univerzitách v Brně a Olomouci, při Katedře mediálních studií a žurnalistiky na Fakultě sociálních studií MUNI koordinuji Centrum pro mediální etiku a dialog.

Spolupracuji také s Nadačním fondem nezávislé žurnalistiky, Future Memory Lab, Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism a Sítí k ochraně demokracie; jsem také členem redakční rady Deníku N a členem Iniciativy za kritickou akademii. Podílel jsem se na vzniku a organizaci konference o etice v dokumentárním filmu v rámci MFDF Jihlava.

Portfolio

Blog

Citát se nenačetl.

Nene.

Podcast

I host Your Gentle Radical, a reflective podcast about what it means to go to the root (radix) of things without turning rigid, cruel, or violent—where radicality meets dialogue, courage meets care, and conviction is tested by openness. Instead of hot takes, each episode follows one honest question long enough to matter, mixing philosophy, thought experiments, and practical ways to act without reproducing the harms we oppose. You can read the project statement and start listening here: yourgentleradical.space and browse the full list of Episodes.

I try to publish about once a month—though real life sometimes wins and the rhythm doesn’t always hold. Recent episodes include topics like Radical, Not Extreme (on radicalism vs. extremism), Common Decency (via Orwell and everyday solidarity), and The Death of God (radical theology as a political and ethical question), each with extras and transcripts on the site. If you prefer subscribing in an app, you can use the RSS feed or listen on Spotify.

Education

I facilitate Cine & Phyto & Upcyclation workshops—hands-on, collective sessions in experimental film and photography shaped by upcycling, recycling, and sustainability. Rather than teaching “mastery” over tools, I frame the process as co-creation with materials, plants, and environments: unpredictability, deviation, and error are treated as part of the method, not a failure. You can see the overall approach and philosophy here: Workshops

I also run workshops for media professionals and journalists focused on ethical growth, advocacy journalism, and building a socially responsible editorial vision. In the past, I’ve collaborated with organizations and teams such as Nesehnutí (including programs hosting Ukrainian journalists), the creators of the Sirény podcast, and Czech Television—creating spaces for reflection, practical tools, and clearer value-based decision-making in everyday newsroom work.

Alongside workshops, I publish my teaching and public-talk materials as a commons resource: the EDU site gathers slide decks, study materials, syllabi, glossaries, etc. Explore it here: EDU (CZ).

Contact

Jan Motal

Katedra mediálních studií a žurnalistiky

Fakulta sociálních studií, Masarykova univerzita

Joštova 10

602 00 Brno

Czech Republic

E-mail: honza.motal@gmail.com

Nevolejte mi / do not call me. Proč → být neustále k zastižení není normální / it is not normal to be on phone 24/7.

Studující se mohou hlásit na konzultace zde: konzultační systém